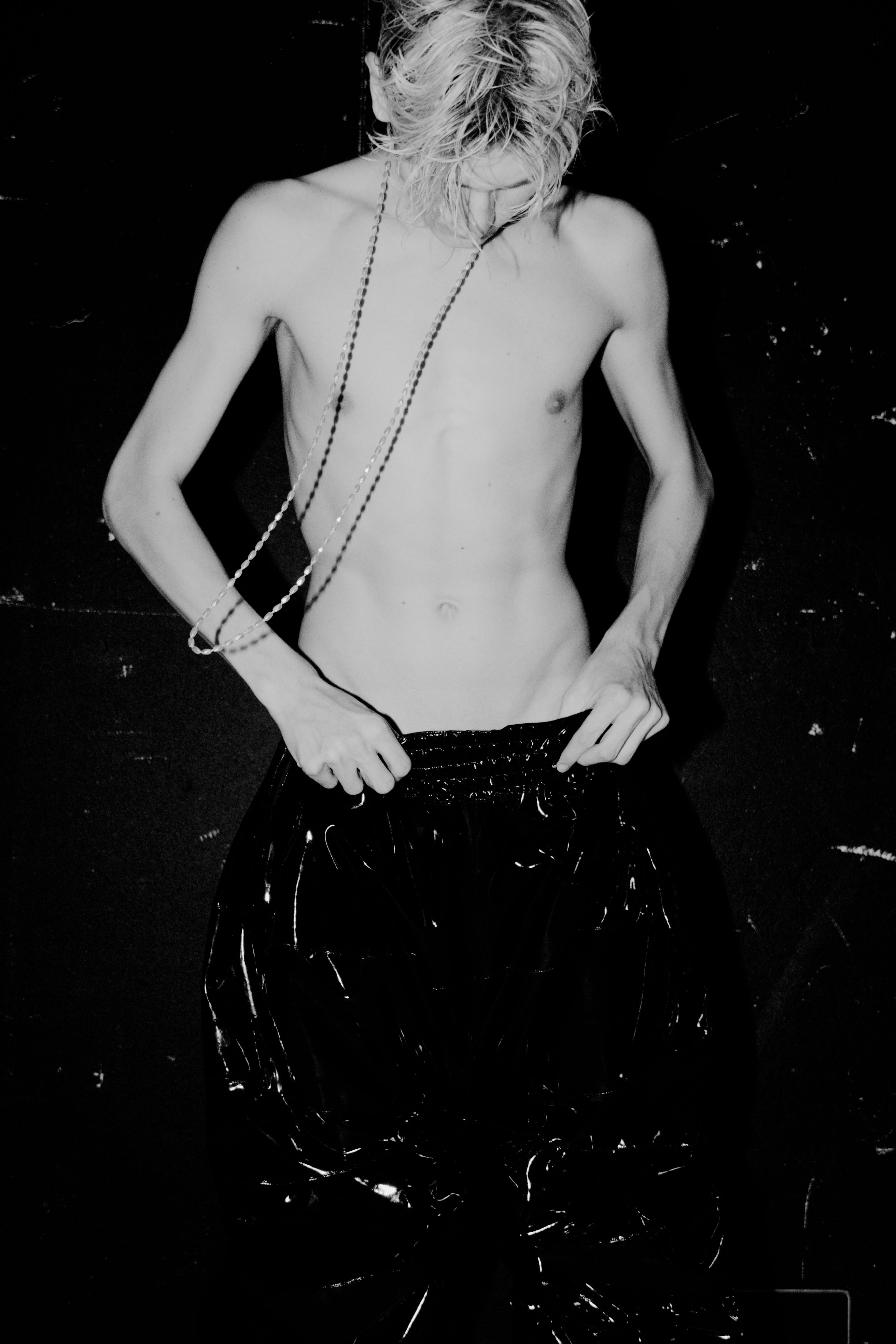

Clare Hewitt is a London based documentary and portrait photographer. After completing a degree in law Hewitt took the biggest change in her career to study photography, finding that both subjects relate in various ways, Hewitt’s personal work uses photography to explore the habits, behaviours and interests in what is a complex interest in human beings. The images featured are from the emotional and honest series Eugenie. Suffering from a stroke which left her severely visually impaired and stole large parts of her memory, Clare Hewitt has captured the reality of human imperfection, experiencing the anxiety, grief, sadness, relentless frustration, her strength and determination and joy. Hewitt describes as Eugenie became a vessel, a friend, who allowed her to produce a series of emotional observations of both Eugenie and herself without a sense of narrative or linearity.

I think it would only be right to start this off with asking how you made the move between studying law to commercial photography and why?

When I was at school I loved art and design & technology, but regrettably they were subjects that weren’t encouraged. I was academic and interested in law, so that seemed like the natural pathway at the time. My parents bought me a Polaroid camera when I was around ten years old, and I remember being really attracted to the idea of photography and light.. Just as I started my law degree at Oxford Brookes University, my grandmother bought me a 35mm film camera for my birthday and I signed up to a night course in photography at the University. I learnt how to develop and print my own pictures in the darkroom and I loved everything about it, especially the smell. The whole process was magical, it still is.

I went travelling to Cuba, Mexico, America and New Zealand after university and planned to be away for three years, but my grandmother became very ill and I came home after three months to be with her. She died a week later and that instigated a change in my perspective. I’d seen or spoken to her practically every day of my life, and adjusting to being without her was complicated. I worked in family law for a year but I felt strangled in such a competitive environment and as I became emotionally attached to cases and clients, I was scared I would become heartless. I didn’t feel like myself.

I’d continued to make pictures throughout university and travelling, and took a big chance on leaving the beginnings of a career in law and applying to the Arts Institute at Bournemouth to study photography. I didn’t know it was possible to have a career in photography at the time, but instinctively it felt like the right thing to do. Photography opens doors to places I could never have imagined being, and like law it allows me to study the complexity of human beings, but much more creatively and freely.

It allows me to study the complexity of human beings, but much more creatively and freely.

Within your work you have this amazing talent to capture personality and emotion, take your Eugenie series for example, you mention that this series became your own emotional response to her adaptation, what is your perspective on the photographers gaze and do you find that you attach your own emotions and perspectives within many of your work or try to detach yourself?

Thank you. I think emotion is central to my work now, and has definitely become more so recently. In Max Kozloff’s The Theatre of the Face he discusses the effect that the photographer can have on a sitter, and how this differs depending on the photographer’s approach. He uses August Sander, Richard Avedon, Mike Disfarmer and Diane Arbus as examples. They are masterful in representing their sitters in particular ways, and I perceive them to use emotion as an instigator for their process. This book influenced me greatly.

In relation to Eugenie, she suffered a stroke in her forties that left her severely visually impaired and stole large parts of her memory. In truth, I met her at a time when I was experiencing my own darkness through grief due to the loss of my grandmother. My camera allowed me to stare at Eugenie and immerse myself in her anxiety, grief, sadness, relentless frustration, her determination, strength, fragility, and joy, without her looking back at me. I’ve never worked in this way before, and it was liberating but also carried responsibility because I knew Eugenie would never fully see the pictures and I wanted to be as sensitive to that as I would be if she could.

I therefore invited the reality of human imperfection to seep through my lens, revealing as much as I could about Eugenie and myself with honesty, and I stopped trying to fill the void between expectation and reality. The work is centred around Eugenie, her experiences, and my emotional experience of observing her, but I’m also aware that my grandmother is in every picture. I think we can represent shared truths through photography, and I certainly tried to achieve that with this work.

Hours with Tim Andrews is a particular series that fascinated me, how did you come up with the concept and do you plan on doing more within this series?

When I was studying at Bournemouth I made a piece of work called Miss Logan in which I spent time with a lady who had Parkinson’s Disease. I remember going to visit her friend with her in a care home, and during our visit she saw a man who had Parkinson’s at a much later stage than her. He was unable to feed himself, talk or move. The shock and fear in her face stayed with me. It was incredibly sad to watch her visually comprehend how she might deteriorate. There was something vital about the passing of time and fear of the unknown that was physically happening to her in front of me.

At the time Tim and I worked on this portrait, I had been looking at David Birkin’s Confessions, in which he asked sitters to make a self portrait and reveal a previously untold secret to the camera. The exposure lasted the length of time it took the sitter to tell the secret, and because there is no sound, the images became a visual representation of the sitter and their confession. I was inspired by these images and the occurrence with Miss Logan, and I wanted to explore this idea around time within the limits of mine and Tim’s exchange.

We settled on five hours and although I didn’t direct him, I was keen that he should continue with very basic, instinctual behaviours during the shoot. He ate his lunch, fell asleep, sat naked, communicated on the telephone. As well as the stills, I produced a time lapse film of the five hour experience, and in it you can see his muscles in spasm, which became less intense once he took his medication, and worse again later into the shoot. It was a fascinating experience. I’m keen to make more of these in the future, perhaps over longer periods of time, 12 hours, for example.

You have had great success with commissioned work from The Independent Magazine, Oh Comely and The Quarterly to photographing some of the biggest names such as Jack O’Connell and even Prince Charles, what was your first major commission and how did you feel?

In 2012 I attended Hellen van Meene’s portraiture workshop at the International Summer School of Photography in Latvia. The following year, one of the portraits I made there was selected for inclusion in the Taylor Wessing Portrait Prize at the National Portrait Gallery. During the private view I met Annalee Mather, the Picture Editor of the Independent Magazine, and the following week I went to show her my portfolio.

We formed a good relationship, and the month after she gave me my first commission, a portrait of singer and political activist Angelique Kidjo. I was incredibly nervous, but I really enjoyed it, and it was wonderful to see the portrait in print for the first time! I’m extremely grateful for that opportunity, and Annalee has been very supportive of my work since.

Through working with charities such as The Butterfly Foundation and the Haringey Phoenix Group and meeting people who have suffered from emotional and physical changes and abuse, what do you feel is most important to a photographer when approaching topics such as these and would you suggest that photographers get more involved with charities?

I think for photographers approaching those subjects it’s important to be sensitive and empathetic and human. What’s interesting to me in this subject matter is the fragility of life, and how people respond to that. I try to have respect for that concept when I make photographs.

I’ve personally found that charities are a good starting point for my projects because they allow access to human beings I might not meet in other circumstances, but it’s very much an individual preference.

Photography opens doors to places I could never have imagined, and like law it allows me to study the complexity of human beings, but much more creatively and freely.

How would you describe your approach to portraiture what do you look for? And do you take a similar approach for stories and the narratives within your work?

Ideally I strive to create something complex through a very simple form. I take a quiet approach. If I’m working with a sitter I don’t like to direct them too much. I think the most interesting and beautiful thing is the way a person is. More and more, I try to be present.

My process is very important to me. I shoot everything on film, which encourages observation and a steady or slow pace. I look down into my camera, or from behind a 5 x 4 under a blanket, which allows me to observe semi-unobtrusively. I have the same approach to all my work, but with narratives I think it’s important for me that they’re not linear. I identify with them more inherently if they’re based on emotion or memory.

You have had great success with commissioned work from The Independent As students leave university this month, what advice do you have for photographers starting out and what are some the things you have learnt over the past few years?

For me it was important to turn upside down some of the technical skills I’d learnt at university so that I could explore my own visual language. When making Eugenie, I was keen for the photographs to be out of focus, over or under exposed, unconventionally composed. I was making that work during spare hours grabbed between assisting and working other jobs, but however you do it, it’s really important to keep making work, to always make time for your creativity, and to pursue any ideas regardless of how far you get with them.

It’s also really helpful to create your own networks, either through attending photography events, private views, exhibitions etc. I am part of a collective of ten photographers that have been meeting regularly for the past 18 months to show and discuss work in progress and completed projects. This concept of peer mentoring encourages you to make photographs and gain different perspectives and insight. If the network doesn’t exist already, make it yourself. Don’t just be sociable on social media, make sure you are present in person.

After graduating in 2010 I also surrounded myself with photographers that I admired and assisted as many people as I could in order learn from them and get a better understanding of where I wanted to place myself within the industry. That proved invaluable.

Financially I’ve found it essential to have multiple income streams in whatever form suits, so that you can always pay your outgoings and continue to be creative, particularly if you choose to be based in London. The most important thing I have learnt is to be patient and resilient. Every little thing you do can contribute to your practice and career in ways you can’t imagine yet, so keep going, no matter how small your steps sometimes feel.

What are you working on next?

Over the past two years I’ve been seeing a psychotherapist each week. Psychotherapy stimulates the subconscious, sometimes initiating dreams and nightmares. The process of visualisation (revisiting dreams through meditation) during my sessions has exposed aspects of creativity that were completely unexpected and overwhelming, and through that I have begun to create Solutio. In alchemy, Solutio is the process of turning a solid into a liquid, whereby the solid changes form but never completely disappears. In psychotherapy, Solutio refers to a similar process of dissolving aspects of the self in order to re-emerge in a more stable and resilient form.

I feel a desire to replicate this state in photography, to visually articulate my dreams, nightmares, and transformation. I’ve begun to create a series of portraits that are large format multiple exposures, repeatedly shooting on the same sheet of film so that the separate elements of the picture seem to dissolve into marked aspects of the whole photograph. Accompanying these are still lives representing aspects of my dreams.

Through my experience of psychotherapy, in 2015 I started to go walking with my large format camera in order to process my thoughts and feelings. I made pictures on these walks, but I didn’t feel fulfilled in making them for myself. Around the same time I heard about Human Writes, a charity that encourages people to write to prisoners on death row in the US. I began writing to a prisoner on death row in May 2015, sending him large format landscapes with each letter. He responds to my letters and sends back his own artwork. The photographs become part of his cell, which is 8’ x 10’. He spends 22 hours a day in it and is allowed out into the yard for two hours a week.

We began this project based on the notion of no judgment between us, and I don’t know why he is on death row. I intend to continue this exchange of written and visual dialogue until one of us is no longer able to. The work is called Kamera, the Russian word for prison cell.