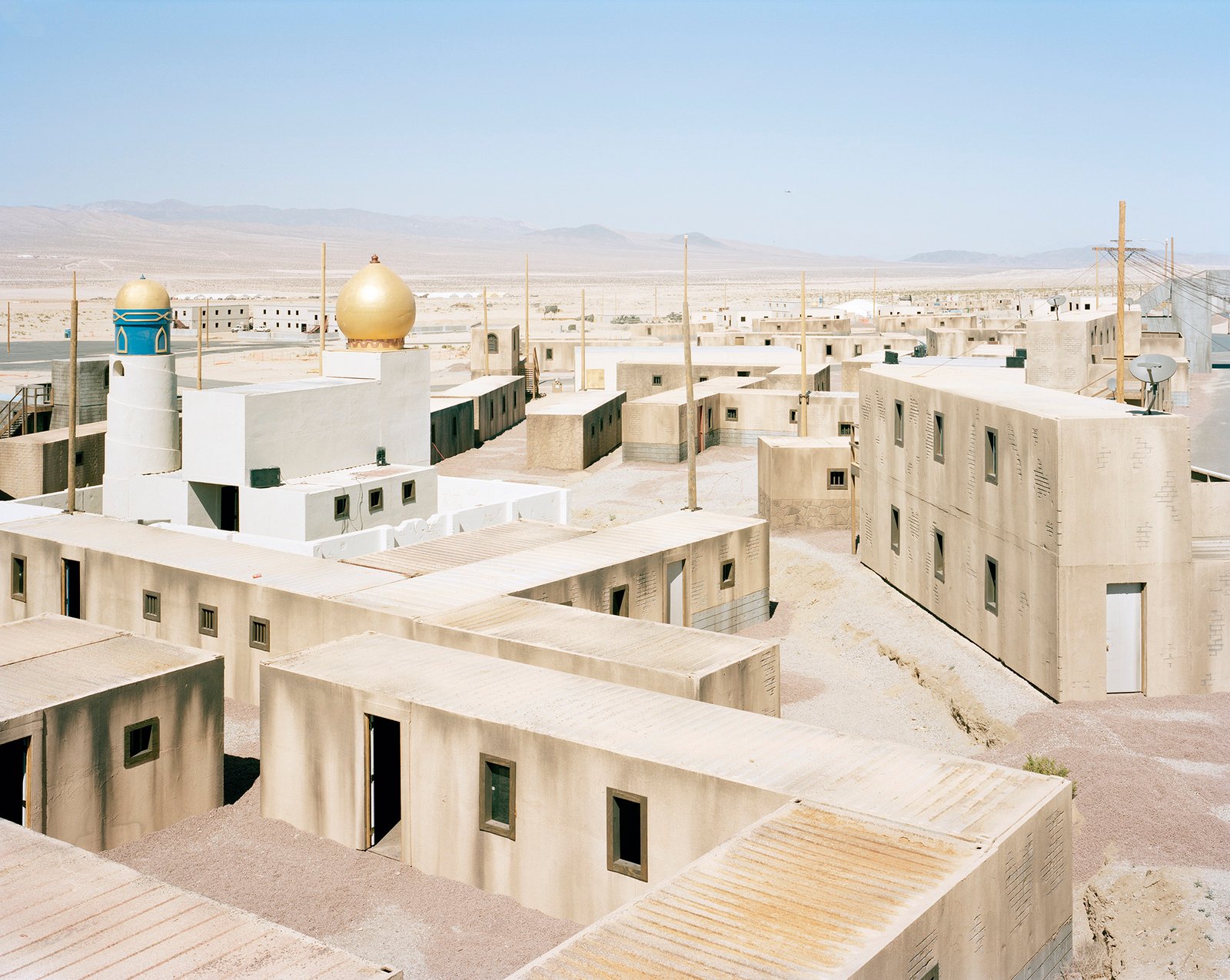

The photographs in Claire Beckett’s Defense Language series features costumed role-players, intricate Hollywood-style sets, and staged scenes on military bases throughout the United States. Between 2006 and 2023, Beckett embedded herself on these bases to examine how Arabs and Muslims were represented during counterinsurgency training for the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Those shown in the photographs include military personnel who were often combat veterans acting as enemy combatants, and immigrants from Iraq or Afghanistan who were brought in to increase the realism within the exercises. The images range from formal portraits and landscapes of improvised, constructed environments to more candid moments of individuals interacting within the training scenarios.

Hi Claire, it’s lovely to be talking to you about your work. Firstly I’d just like to say how beautiful the work you make is but also when coming across your work on the whole, how wildly complex your projects are when you dig deeper into the narrative. What drew you to making this series?

Hi Jonny, it’s great to be talking with you about my work, and thank you for your kind words.

I was drawn to make this work as part of a larger critical engagement with the American wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. When I discovered the work that would become the Simulating Iraq project, I had been making portraits of young soldiers in training for a couple of years already for my project In Training (2004-2007). I was walking through the woods while photographing soldiers during Basic Training exercises when I stumbled upon a trio of young female soldiers wearing odd faux-Arab outfits over their military fatigues. Right away, I knew that I was looking at something problematic, but I had no idea what it was. I went back home and did some research, and realised that it was a US military-wide mandate to address the type of asymmetrical warfare that American troops were up against in Iraq and Afghanistan, basically that the military needed to learn to fight against small-scale insurgent groups. And I learned from reading a Rand Corporation (right-leaning American think tank) strategy book on the subject, that these trainings were going to take place on military bases across the US and that the military decided to bring a Hollywood-style sense of culture to bear on the training is what really piqued my interest.

You mention the problematic depiction of ‘cultural others’ in these trainings and how this project challenges the implicit assumption of American cultural superiority. Can you tell me more about that please?

I realised that contained in these training sessions was a whole basket of American stereotypes about Arab and Muslim people, and that perversely the military training environments were providing a kind of mirror into these stereotypes, and into our culture more broadly. You can see the problematic depiction of Afghans and Iraqis in the overly simplified “us” versus “them” mentality of these places. The cultures and languages are not engaged with in any depth, but instead in a purely surface-level manner. I’ll give you an example that relates to how Islam is depicted in the training environments.

In addition to the Simulation Iraq project, I have another series, The Converts (2011-present), that also deals with Islam in America. It’s a project about Americans not born into Muslim families who have chosen to become Muslim. In order to make The Converts, I have spent a great deal of time in American Muslim communities and learning about Islam (I am not Muslim). The intersection between the two projects is essential to the interpretation of the Simulating Iraq photographs, because what I’ve learned from American Muslims has hugely informed the way that I read the pictures of faux-Islam found at the training sites.

I’ll direct your attention to the photograph Shi’a Mosque, made in 2008 [the last image in the series].

It’s a photograph of a mock mosque in the training environment at Fort Irwin in California. There was a symbolic visual language in this training environment that served the purposes of military training but did not necessarily reflect reality. For example, in this particular village, Medina Wasl, there were multiple mosques. In an attempt to make troops aware of the difference between Sunni and Shi’a Muslims, their interest being tactical, not theological, as the different Islamic groups had different military allegiances. And in a move of basic symbolic logic, the more powerful group was always represented by a larger mosque. In this photograph, I’ve shown the smaller mosque belonging to the less powerful Shi’a group. This straightforward representation of the power differential was specific to the training environment and did not necessarily mirror the real world.

Additionally, the photograph features a striking green chair with a vaguely Islamic feel. This “mosque chair” was another defining characteristic of mosques in this training environment. If you saw a chair of this shape, you would know you were in a mosque, and the chairs varied in colour, including white, orange, and green. So you might also say you were at the green mosque or the orange one. However, this “mosque chair” is another bit of visual language unique to this training environment. Real-world mosques do not have such a chair, although they do, at times, contain a raised platform or pulpit.

I find it fascinating that the US Army would allow the public to witness this. Do you think there’s a reason behind them allowing you to document this or do you think again it comes down to the assumption of American cultural superiority?

When it comes to my access to these facilities, there are a couple of variables that are worth understanding. First, through working with many military public affairs officers, I’ve come to understand that the military basically believes it exists to serve us, the American people. And part of that service is to be open to showing the American people the work that they do, and so by extension, that reasonable requests from photographers, artists and journalists should be honored. So I was the beneficiary of this commitment to openness. Also, it’s worth remembering that nothing I photographed is top-secret or required security clearance. It was all out in the open, to be seen by visitors and soldiers alike.

Second, it’s important to understand that the military was very proud of the training they had created, and they were eager to show it off. Early in the project, I called a Marine Corps public affairs officer to discuss gaining access to a training, and she said, “Ma’am, it’s win, win, win when we partner with the arts communities.” I remember thinking at the time, how does she know that we call ourselves the “arts community?” The point being, for whatever reason, there was some awareness in the military hierarchy that it would be a good thing to have artists in to see what they were doing.

It’s also interesting that often combat veterans were playing the role of enemy combatants–imitating people from Iraq and Afghanistan. Were these actors from the US and had fought in the invasion of these countries?

There is quite a mix of people playing different roles in the photographs, including local civilians, people from Iraq and Afghanistan, and combat veterans. But when speaking of the combat veterans specifically, yes, they were soldiers who had previously been deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan. Sometimes they were doing kind of bland things in the trainings, like pretending to be a government official, or a vendor in the market, but more often, the veterans had more active roles as pretend enemy combatants. The goal was to have highly skilled soldiers with combat experience in Iraq or Afghanistan serve as the enemies for the soldiers undergoing training to fight against. The idea was that the better the faux enemy could fight, the more effective the training would be.

I’m interested in your personal relationship towards this project and the people you’ve photographed for the series. The images are so intimate and moving in a lot of ways, yet so strange when you break down what’s going on in them.

Yes, it’s true, there is both an intimacy to the picture-making when it comes to the portraits, and at the same time a larger social critique that permeates the work. I would say that I am first and foremost a portraitist, so the pictures always came from a place of wanting to know something about the people I was photographing, and also wanting to honor them in the way that they are depicted.

It’s also worth noting that I never wanted the critique to land on the individuals that I photographed. The problems that the photographs reveal are not the fault of the people that I photograph. Rather, the blame lies with the larger culture.

The work was made over a large period of time (2007-2023). Why did the project keep going on for so long, even after the US pulled troops out of Iraq and Afghanistan?

The bulk of the photographs were made while the wars were ongoing. However, as I began editing the work for the book, I learned of an additional training facility that had a really interesting approach to the cultural aspect of training, so I went back to make the final pictures there in 2023. The drills were essentially over by 2023. The site I visited was still used for training, but not for preparation for deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. In fact, the site was so disused that I was told to visit in late spring, after the spring thaw, but before it became overgrown with vegetation. The base is in upstate New York.

With the final images being made for this project in 2023, is there anything you’re looking to work on next within the same realms?

Up next, I plan to complete my project, The Converts, about American converts to Islam. I also have a few other things under development, and yes, something completely new, so stay tuned!